Bye Russia: Russian emigration of the twentieth century

Russian poet, essayist, and Nobel Prize winner in literature in 1987 Joseph Brodsky said in one of his speeches: “Russians have the largest nation yet are the most divided and scattered around the world”. Joseph Brodsky was born in 1940, almost in the middle of the century, equidistant from all the dramatic events of Russian history of the 20th century which became the main catalysts for Russian emigration.

In Russian historiography, Russian emigration can be divided into 5 waves. Of course, one cannot say that the Russian emigration is only a product of the 20th century – people emigrated from Tsarist Russia as well, but those were rather individual cases.

The first wave of Russian emigration

The first wave of Russian emigration happened during the days of the Russian revolution of 1917. This period – the edge between the “old tsarist Russia” and the “new communist one” – became one of the most difficult periods of Russian history. At this time, not only the political system of the country changed, but also its basic life principles. People who could not accept new trends decided to emigrate from the country they loved but which was no longer there.

The first wave of emigrants is often called “white” like the color of the monarchy the supporters of which the emigrants were. That first wave included various segments of the population: aristocrats, princes, representatives of the royal family, bankers, doctors, teachers and scientists, jewelers, manufactures, writers, artists, professors, army officers, soldiers, Cossacks.

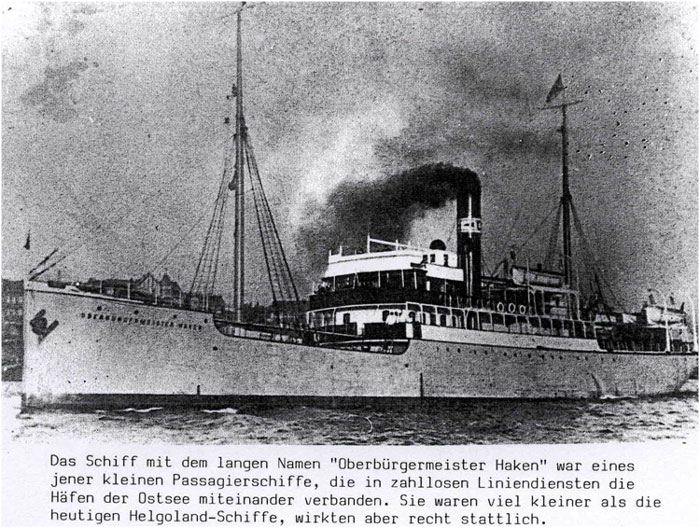

In addition to the mass “independent” emigration, there were also cases of forced expulsion of people from the country. The main motive of forced emigration was the dissidence, people’s personal beliefs that the new Soviet government did not like. The most famous example of forced emigration was the “Philosophical Steamship” – the collective name of two passenger ships voyages that brought 260 representatives of the Russian intellectuals, including philosophers, from Petrograd to Shtettin (Germany). The main havens for “white” emigrants became France, Germany and Switzerland, as well as the countries of the Balkan Peninsula which emigrants reached after a long journey from southern Russia to Turkey and, finally, to the Balkans.

It was legal to leave the Land of Soviets until 1929, after that the Iron Curtain descended. Historians are still not able to count the number of people who left the country during that period, different figures are mentioned, from 1.5 to 2 million people.

The second wave of Russian emigration

The second wave of Russian emigration happened during the Second World War and the first post-war years. At this time, a few groups of people found themselves in emigration lines:

– citizens who had to fulfill the treaty obligations of the USSR in Germany,

– the interned ones (merchants of the merchant fleet, prisoners of war, people forcibly taken out by the Nazis to carry out labor work),

– and the last group of emigrants consisted of Nazi volunteers (police, Vlasovites, Bandera, etc.).

About 10 million people in total ended up abroad at that period. Many of those who remained in the West did not return out of the fear of getting into the Stalin’s camps. This wave of emigration is characterized by the fact that most of the emigrants settled not in Europe, but in the countries of South America, as well as in Canada and the USA.

The third wave of Russian emigration

The second half of the 20th century in Russia was marked by a significant softening of the political regime. After Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev came to power and set the course for the democratization of Soviet power. He was remembered as the author of the “thaw” – a period when the pluralism of opinions became relevant again. But after his resignation in 1964, he was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev who did not fully share the Khrushchev idea of “thaw”. That served as a continuation of the confrontation between the authorities and the intelligentsia.

It was during that period the third wave of Russian emigration flourished. Russians from Germans, Armenians and Jewish descent, left the country. It was formally national and ethnic emigration, but in reality totally political. The theatricality of the action distinguished that emigration from the two past waves. A person who wanted to leave the USSR had to receive a fictitious invitation from his foreign relatives. Sometimes the state security agencies prepared such documents themselves, and the emigration turned into a forced deportation from the country.

The third wave of emigration reached its apogee in the early 1970s. The route of all departing ones was standard: Moscow – Vienna. Vienna at that time served as a connecting point between the USSR and the rest of the world. The Soviet government did not care about the further fate of its citizens, the invitation was, as we have already said, only a formality. During this period, many writers and poets, directors, philosophers, and theater artists left the country. Most of them settled in the United States, a smaller part of the emigrants settled in Europe and Israel.

Also at that time another group of emigrants appeared, the defectors, i.e. people who refused to return to the USSR from their legally approved trips abroad (political and business trips, concerts, conferences, etc.). Most often those were the people close to art. The most famous defectors of that time are: ballet dancers Mikhail Baryshnikov, Alexander Godunov, and Natalia Makarova; composer Mstislav Rostropovich; opera singer Galina Vishnevskaya and others.

The fourth wave of Russian emigration

The 90s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, became a new time for emigrants. This fourth wave of emigration has become the most heterogeneous. Among those who left during that period were not only intellectuals, but also ordinary people who wanted to normalize their financial conditions. For this group of people, emigration was both short-term and long-term. In addition to financial and labor emigrants in the 1990s, many repatriates left to Germany, Finland, Greece, Israel and other countries. The 90s were a transitional and a very difficult time for Russia, so the registration of those leaving the country was not conducted, and now we can only assume how many people left the country during that time.

The fifth wave of Russian emigration

The last and fifth wave of emigration happened in modern Russia. Its main characteristics are non-spontaneity, small size and thorough preparations. If emigrants of the first and third waves were forced to leave the country in a hurry not knowing what awaits them further, modern emigrants are carefully preparing for the move: they learn the necessary foreign language, get education, participate in various exchange programs and internships, establish personal and professional contacts in the country of their planned stay. In addition, modern emigration is not dramatic: people know that they can always return to their homeland to visit their loved ones or stay here again (which some of them do). Representatives of the previous emigration waves were deprived of this “advantage”.

It is also important that the reasons for emigration have also become very diverse: study, career, scientific activity, marriage. On average, about 100 thousand people leave modern Russia a year.

Conclusion

Emigration – behind this word are the lives of millions of people. Despite all the difficulties, especially adaptation to a new country, many expatriates sought and keep seeking to preserve their cultural roots, traditions, and introduce the world to their culture. Emigration of the 20th century was a personal tragedy, but Russian emigrants made and make a huge contribution to the development of our global community. If you are interested in learning about the input of Russian emigrants in the world heritage, let us know in the comments!

Culturologist, professor of Russian as a foreign language and promoter of Russian culture.

Aleksandra gives Russian lessons via Skype.