Life in post-revolutionary Russia: NEP and new cultural trends

In 1917, the life of Russia changed dramatically – the February, and then October Revolutions, presented the world not only a country with a completely new type of political architecture, but also a new format of cultural life which still amazes by its diversity. Architecture, fashion, theater, literature, visual arts, education – all these spheres have undergone fundamental changes in post-revolutionary Russia. Why? Let’s investigate it together!

NEP

In the spring of 1921, after the difficult and economically destructive years of the policy of War Communism (1918-1921), the Soviet Government headed for changes in the economic sector. On one hand, this decision was dictated by the need to restore an economically weak country after the civil war, but on the other hand, it was somewhat spontaneous as the Soviet Government did not have any clear plan of actions. As a result, a new economic policy – the NEP – emerged and during its few years of existence was not only able to consolidate the country but was also marked by a wave of Liberalism.

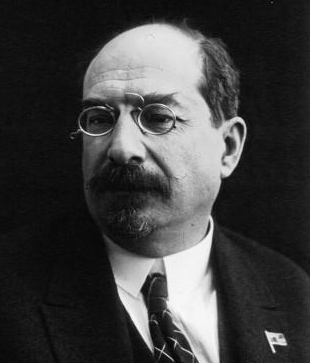

During the NEP, the person responsible for the entire spectrum of culture was Anatoly Lunacharsky. Occupying the position of the Commissar for Education he practically let the artists do whatever they wanted. This meant that not only the new and “ideologically correct” artists participated in cultural life, but also artists of the tsar’s era.

Education

The Bolsheviks began their transformations with the sphere of education. The population of the new Soviet Russia consisted mainly of peasants who could not read and write, so compulsory primary education was introduced. These measures allowed to increase the percentage of literate people, first up to 70%, and then up to 95%.

Interestingly enough, not only did children and adolescents attend schools, but evening schools were created for workers where adult specialists studied all the necessary subjects: from Russian language and Literature to Mathematics and Geography. The most talented, successful and promising students of all ages continued their studies at colleges or universities. Of course, all this was done for a clear reason: The new government needed skilled workers who could bring the country’s scientific and economic potential to a new level. In addition, as many people as possible should have been able to read and understand the Bolsheviks’ propaganda.

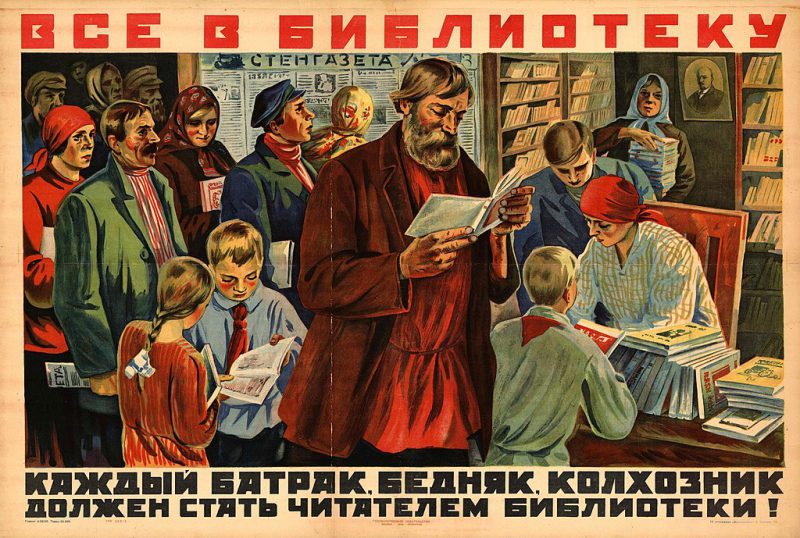

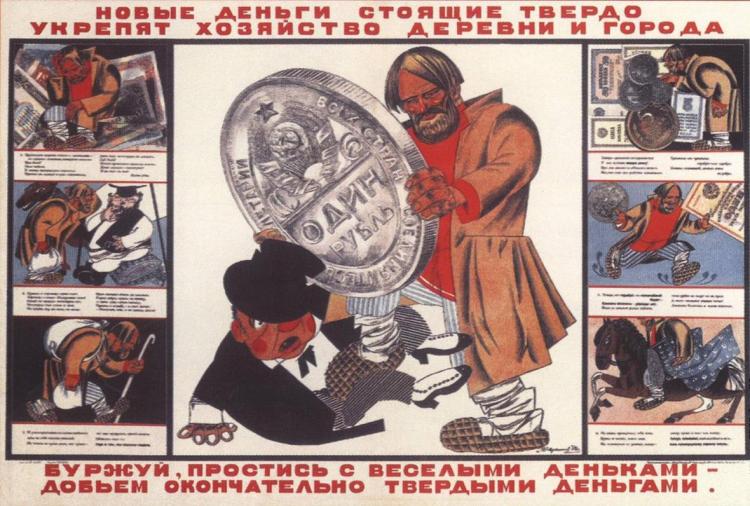

Propaganda posters

However, teaching the population to read is a long and complex process, while propaganda needed to be transmitted continuously. What to do? Use the images, of course.

Just as the Catholic Church created stained glass windows – “The Bible for the illiterate” – so did the Soviet Government by beginning to actively use the art of the poster – vivid sketches of everyday life with brief but informative slogans that informed the population about the Party’s policies.

Paintings

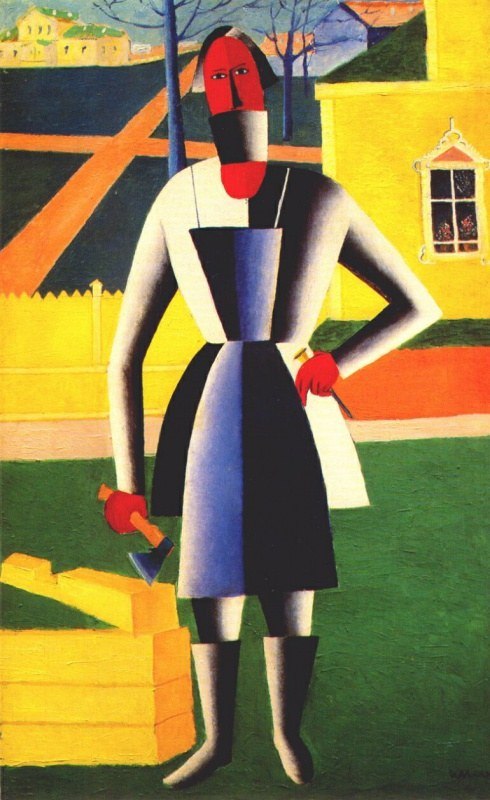

Along with the art of the poster, painting also flourishes. Moving away from all previously accepted canons and movements, artists showed the world new forms, images and colors.

Artist associations appeared here and there with names that were fully consistent with the style of Soviet abbreviations: “Unovis” (Approvers of New Art), KORN (The Team for Advanced Observation), MAI (Masters of Analytical Art) and others. Their paintings, comparing to pre-revolutionary style, became graphic, full of geometric shapes and gave a lot of room for interpretation.

Artists also collaborated with theaters and various troupes creating not only costumes for performances, but also decors.

Theater

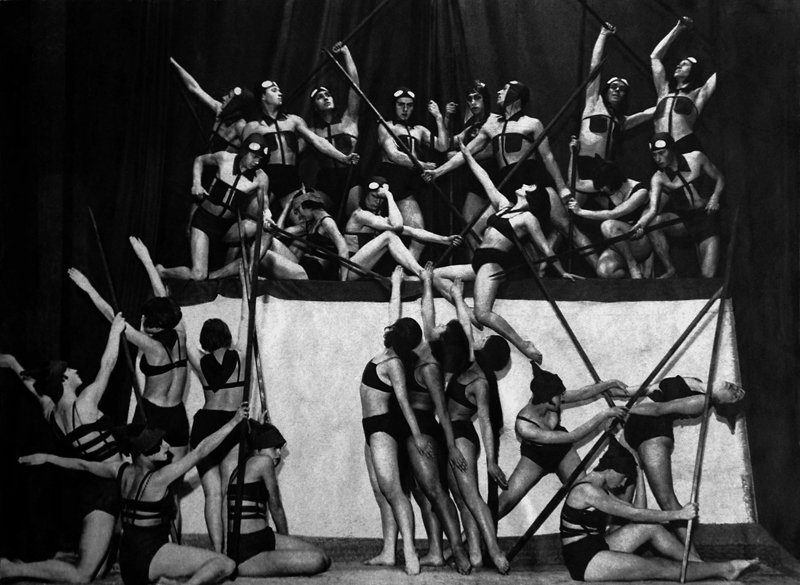

The theater Art in this era was undergoing major changes and rebirth as well.

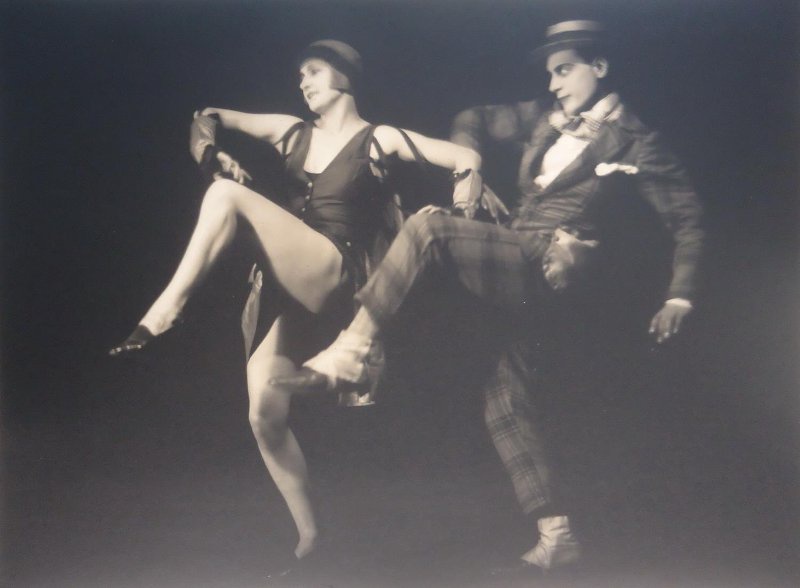

The theatrical era of the NEP period is inextricably linked with the name of Vsevolod Meyerhold. He created a new acting system called “biomechanics”. It appealed not to the usual psychologism of performances but aimed to create a truly new world on stage. Actors in the Meyerhold Theater did not learn long lines and did not study the personality of the portrayed character, but studied the ease of movement and even acrobatics. The main elements of the action on the stage were plasticity and movement that speak louder than words.

“The viewer should feel the tragedy without many words about the tragedy,” said Meyerhold.

“Criminal romance”

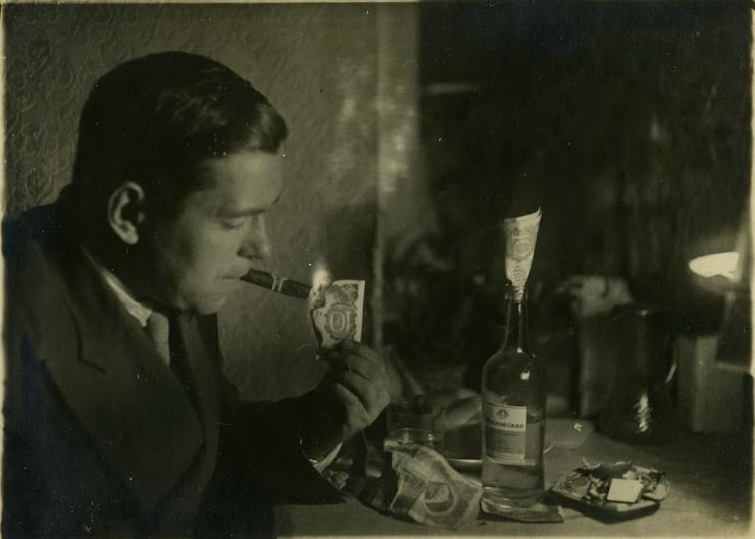

Such radically new ideas, however, were not always understood by ordinary people, who did not want to search for the hidden meaning of the phantasmagoria depicted on the theater stage or the artist’s canvas. So often people preferred to spend their free time in taverns or inexpensive restaurants where it was possible to dance to “indecent” (for that time) Western dances – Foxtrot and Charleston – and listen to songs in the style of “criminal romance”.

This new song genre began to emerge during the 1917 Revolution in Odessa which was known for its regular criminal reports. Odessa became the motherland for the songs about NEPmen, bandits, detectives, and prisoners.

One of the most popular songs of those years was the song “Bublichki” (Bagels) telling a story of a poor girl selling bagels in the street. Surprisingly, these criminal songs easily entered the everyday life of Soviet people and remained popular for a very long time.

Song “Bublichki” by Faina Nicholas (modern performance)

Cinema

Cinema also contributed to the strengthening the criminal songs positions.

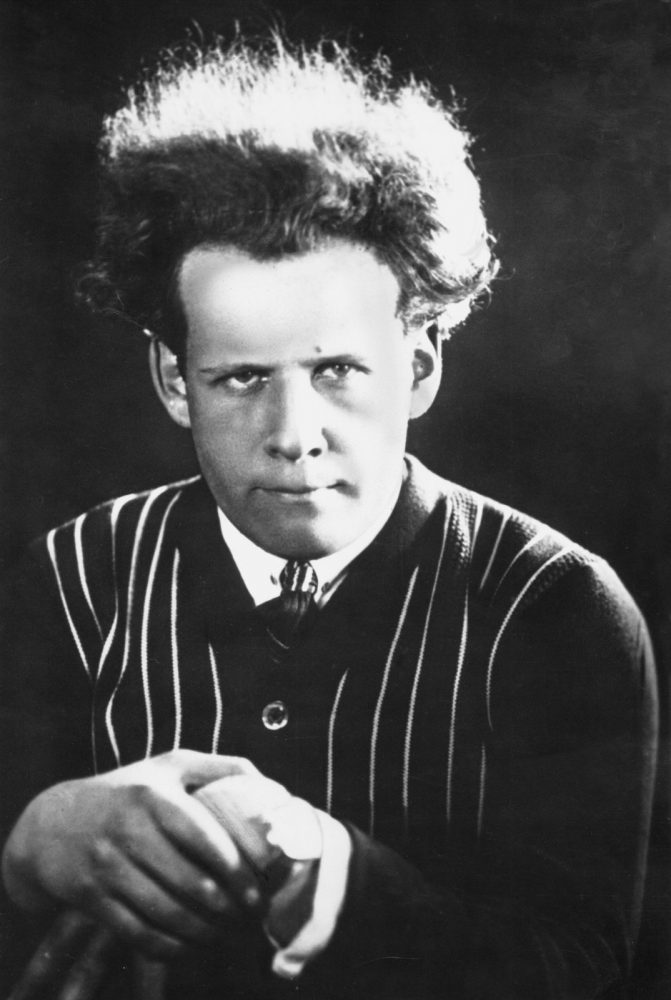

Speaking about the cinema of the 1920s, it is impossible not to mention the name of Sergei Eisenstein – the legendary director of black and white cinema. His large-scale movies “Battleship Potemkin”, “Alexander Nevsky”, “October” “Ivan the Terrible” are still on the list of black and white film masterpieces.

But Eisenstein’s films were not intended for a wide audience, therefore, parallel to Eisenstein’s epic films, simple, “down to earth” films about the lives of ordinary people were made. They included sketches of everyday life and ideological struggle. The criminal songs were used as soundtracks for those movies along with the melodies composed specifically for them. Some of those movies are: Cutter from Torzhok (1925), Prostitute killed by life (1926), House on Trubnaya (1928), Rivals (1929), and others.

Fashion

The movies of that era, along with other sources, became also a source of knowledge about the appearance of the first Soviet citizens.

The bohemian Soviet elite preferred to follow Western trends in fashion, while ordinary people drew inspiration from the past revolution.

It is most interesting to study women costumes of that time, since women had divided into three camps. The first camp were women from rich, bohemian or creative families who, on one hand, sought to emphasize their femininity by wearing dresses (albeit in a new fashion with a very low waist), hats (the look of which was very peculiar) and high-heels, and on the other hand, these same fashionistas tried to show their neglect of fashion.

The second camp included women revolutionaries who saw their lives in the struggle for communist ideals. These women were characterized by a black leather jacket of male cut several sizes larger than the woman herself, as well as a scarf that hid the woman’s hair. These clothes made it possible to level out their gender identity, focusing on the functions performed.

Finally, the third women’s camp absorbed all those who were not a fashionista or an ideological worker. Times were hard and there was no money for new dresses, so women altered their old dresses trying to at least slightly correspond to the spirit of current times.

Conclusion

In 1929, Lunacharsky was removed from his position. This coincided with Stalin coming to his sole authority and the beginning of a tougher policy both in the field of art and in other spheres of life. The era of experimentation and the peaceful coexistence of the old and the new ended.

The NEP era – by historical standards – was very short; lasting only seven years. But the cultural changes and trends that appeared during that period turned out to be so deep that it is impossible to talk about them in the frame of one article. We hope that you enjoyed this article, and if you want to learn more about the NEP culture, write to us in the comments!

Culturologist, professor of Russian as a foreign language and promoter of Russian culture.

Aleksandra gives Russian lessons via Skype.